By Muriel Mirak-Weissbach

POTSDAM, Germany — In June 2018 a leading Armenian association made headlines in Germany, after it was formally announced that Armenian philanthropist Noubar Afeyan was donating 200,000 euros from the Aurora Humanitarian Initiative to a project to reconstruct a historical church now lying in ruins.

The Court and Garrison Church in Potsdam, as its name betrays, is a church constructed originally for members of the royal court and military to worship. It was built by architect Philipp Gerlach from 1730 to 1735, on orders of Friedrich Wilhelm I, who was known as the soldier-king. He and his son, Friedrich the Great, were buried there.

In its long and checkered history, it has been destroyed and rebuilt more than once, the architectural victim of shifting political fortunes. At the end of World War II, on April 14, 1945 it was bombed by the British and the nave and bell tower went up in flames, leaving only the external walls intact. With repairs, it was renamed as Holy Cross Chapel in 1949, and was used for services and other parish activities for almost 20 years.

In 1966, the East German Communist regime targeted the building for destruction. Walter Ulbricht, leader of the SED Socialist Unity Party, is quoted as having asked, “What business the ruins had to be there,” and called for it to be removed. He considered it a blemish on the socialist image of the city. Despite protests by citizens, architects, churchmen and cultural historians, the city authorities decreed the elimination of the church by explosion. This took place in summer 1968 and right next to the site they built a Computing Center 1971, which stood as an example of socialist architecture.

The Berlin Wall came down in November 1989 and the regime followed. Soon thereafter Germany was reunified and a long process of rebuilding — political as well as cultural — began. What was to become of the historical buildings still standing? And how should one deal with the monuments to the socialist domination in former East Germany? The church of the Hohenzollern dynasty represented a special challenge.

In 2008, the Potsdam Garrison Church Foundation was inaugurated and joined forces with the Society for the Promotion of the Reconstruction of the Potsdam Garrison Church (FWG), founded in 2004 by citizens of Berlin and Potsdam with the support of church and political authorities. Last June 24, fifty years after the church had been blown up, FWG chairman Matthias Dombert presided over a commemorative service and among those attending was Harout Chitilian, representing Aurora.

The Aurora Humanitarian Initiative was established by three prominent Armenians whose forefathers were among the fortunate few to survive the genocide. Over the past few years it has become well known in Armenia for its annual Prize for Awakening Humanity, which honors an individual whose single actions have contributing to preserving lives, along with institutions that have helped make that individual effort possible. To express “gratitude in action,” Aurora has launched several projects, including scholarships to help refugees, children and victims of conflict and poverty.

Founded in 2015 by Vartan Gregorian, Ruben Vardanyan and Noubar Afeyan, the initiative draws inspiration from the past to encourage efforts towards building a future in which “empathy will replace sympathy.” It is a global movement with activities on every continent.

A Personal Story

In keeping with the profile of the Aurora Initiative, the decision to make this donation springs from a personal story, that of Noubar Afeyan. As he has related the events in several locations, his grandfather and great-uncle were saved from certain death thanks to the efforts of German officers in Turkey during the war. The two Armenians had been pulled out of a hopelessly packed cattle car at a small station called Belemedik, by German military personnel. The officers were deployed on the Baghdad railway project which the Germans were constructing for their Ottoman allies.

Speaking during an Aurora award ceremony in Yerevan last year, Afeyan described his ancestors. “My grandfather had blue eyes and spoke perfect German. Both [he and my great-uncle] worked at the German Industry Bank in Constantinople. The Germans had the best logistics,” he went on, “and hence supported the genocide, but there were also officers who, as Christians, could not agree to this.” It was such officers who supplied his ancestors, Bedros and Nerses, with German uniforms, as well as documents, and employed them for two years in the Baghdad railway project as book-keeper and supply manager. Afeyan’s great-aunt Armanouhi (who lived to the age of 101) never tired of telling him the story to him as a child in Beirut where he was born. Her husband, the doctor Antranig, was protected by “the Ottoman soldiers because he protected them,” she explained. Bedros and Nerses were her brothers. As Afeyan related it to 100 Lives, the two “would go into the trains as they passed through Belemedik to search for people who they could help escape in order to resurrect the Armenian nation — clerics, educators, writers, doctors. Armenouhi said they felt terrible, knowing the other people left on the train were surely going to die.” There would be no diaspora if such individuals like the German officers had not provided protection. “We would not be here without our friends,” Afeyan has said.

The Garrison Church reconstruction initiative caught Afeyan’s attention because the promoters had clearly stated their intention to resurrect it as a site of peace and reconciliation. He intends thus to honor those who saved his ancestors, but also the many more unnamed soldiers who acted according to conscience. Afeyan has referred to many families he knows whose ancestors were saved by German and Austrian soldiers. Krikor Balakian, who later served as bishop of the Armenian Apostolic Church in London and Marseille, is another descendant of Armenians thus spared.

One Symbol, Many Meanings

The plan to restore the Garrison Church has been shrouded in controversy from the start, a controversy that springs from the symbolic value attributed to the edifice and the several changes of fortune the church has witnessed.

The opponents of the reconstruction project denounce the church as a symbol of Prussian militarism and hero worship, associated not only with Friedrich the Great but also with the Nazis. On March 21, 1933, in fact, Hitler shook hands with German President Paul von Hindenburg in front of the church, as documented in photographs. The gesture is seen as emblematic of the fateful alliance between the old Prussian establishment and the new fascist dictatorship, a dictatorship which perverted and exploited Christian values and church authority. Opponents of the reconstruction plan call it the “Cathedral of German militarism.” One further consideration raised against the project is that funds could be better deployed elsewhere; there are other churches in sore need of funds for repairs and renovation, as Detlaf Karg, Director of the Brandenburg Office for Preservation of Monuments, has pointed out.

The opposition has organized to block the initiative, by mobilizing 14,000 citizens to sign a petition calling for a referendum on the project. In addition, in 2015 a group of artists set up a Creativity Center in the Computing Center, in hopes of preventing it — a representative of socialist architecture — from being razed to make way for the reconstructed church.

On the other side are the promoters of the effort in the Garrison Church Foundation, who include prominent Brandenburg politicians and church representatives, like former Prime Ministers Manfred Stolpe and Matthias Platzeck, former Interior Minister Jörg Schönbohm, current Science Minister Martina Münch and Potsdam Mayor Jann Jakobs. Representatives of the German Evangelical Church (EKD) are Irmgard Schwaetzer, President of the EKD Synod, and Wolfgang Huber, former EKD council chairman. Television personality and philanthropist Günther Jauch is also involved.

These promoters and their supporters argue that the church should symbolize peace and reconciliation. Some stress the fact that King Friedrich-Wilhelm I, the first patron of the church, was a city-builder, a reformer and was not — like his son, Friedrich the Great — engaged in wars of aggression. They point to the bright spots in the history of the church: it was the venue for the assembly of the first freely elected Potsdam Council (Magistrat) in 1809, and in 1817, on the 300th anniversary of the protestant reformation, it hosted the meeting of Calvinists and Lutherans who established the Church of the Old Prussian Union. As for the relationship to Nazi Germany, it is recalled that many of the officers who conspired to assassinate Hitler on July 20, 1944, like Henning von Tresckow, were members of this parish. Finally, there is also the argument that the reconstruction is but one part of a broader effort to restore the historical Prussian city of Potsdam to its Baroque splendor, making it worthy of its designation as a UNESCO world heritage site.

People, Not Stones, Make History

But the decisive factor for the promoters is the human factor; as Huber, former bishop of Berlin-Brandenburg, put it, “The question is not, must the tower be rebuilt? The question is, should it be rebuilt? The opponents say no. I consider this magical thinking, which I as a Christian do not accept. The evil spirit of the past does not hang on walls. It was human beings who were responsible for this spirit. Those responsible for continuing this spirit will also be human beings, not walls. So I would be quite devout and would say: this viewpoint is incompatible with my Christian faith.” The church will be what one determines to make of it and how one deals with its historical burdens. For Huber, “Nowhere in a church-related site can one come so close to the disaster of our history as here.” On October 29, 2017, during a service, he said, “The tower should again become what it was for centuries: an architectural symbol in the city landscape,” and “it should become what it never was: a center for peace and reconciliation.” Precisely because of this history, he considers it an important part of the culture of remembrance. The idea is that reconstruction will contribute to remembering the lessons of history, learning responsibility and living in a spirit of reconciliation. The project calls for other activities in addition to church services to be held in the tower, specifically pedagogical and scientific events dealing with history.

The enterprise is underway, as the relevant church and political institutions have agreed, and, as mentioned, the funds are coming in. In 2013 the Garrison Church was recognized officially by the federal government’s Representative for Cultural and Media Affairs as a nationally significant monument, and 12 million euros in federal government funds are to be allocated towards the estimated total cost of 27.5 million euros. The EKD has organized 5 million in loans, and private donors have come up with 10 million. Individuals and groups can make small or large donations: they can sponsor tiles for the tower, at 100 euros each, or contribute 10,000 euros to build a threshold; 200,000 euros can finance a vase containing a flame, and 100,000 euros will pay for the capital of a column. Among the private donors is the Aurora Humanitarian Initiative, in the person of Noubar Afeyan. It is not clear what specifically the donation should finance, but Afeyan’s declared intention is to contribute to express gratitude for those German officers who saved Armenians, in the spirit of reconciliation.

The Other German Officer

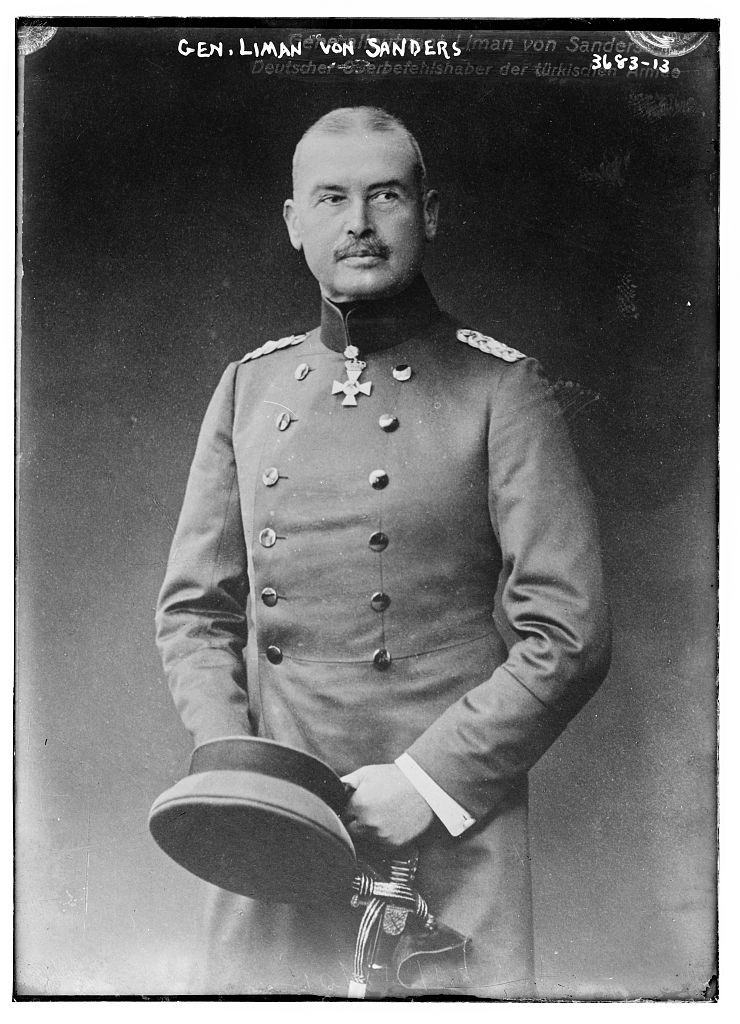

Afeyan may or may not be aware of the controversy around the project. Given the noble intentions motivating their donation, it should be of interest to the Aurora Humanitarian Initiative to learn of another comparable controversy, which involves a famous German officer who saved Armenians from death, as those unnamed officers saved Afeyan’s grandfather and great-uncle. This is the case of General Otto Liman von Sanders, who was the leader of the German military mission on the Bosporus during World War I. Although German officers were not to interfere in internal Turkish policy, Liman von Sanders used his military position to intervene repeatedly to prevent deportations of Armenians and Greeks slated for extermination. In 1916 he threatened the Vali (governor) that he would deploy his own armed soldiers to block a planned deportation of Armenians from Smyrna, thereby saving an estimated 6-7,000 persons. He acted again to stop the deportation of Greeks from Urla and the coastal regions. This is recorded in official diplomatic correspondence and in personal eye-witness reports.

Despite his extraordinary efforts, instead of being recognized after the war, he was framed up and persecuted. In 1919, while en route to Germany with other officers, he was illegally detained in Malta, arrested as a prisoner of war, and released after eight months only after a massive diplomatic effort had been launched to free him. After his death in 1929 he was buried in the Old Cemetery in Darmstadt, his home, and was given an honor grave, in recognition of his military achievements. Recently however, in 2015, he was stripped of this honor, on grounds that it had been conferred “exclusively for his military successes,” and he was even accused of having been involved in the genocide of the Armenians.

The case of Liman von Sanders remains the subject of heated controversy, as competent historians and journalists have joined to demand that the historical record be rectified and his reputation be restored, along with the honor status of his burial site. Given the mission of the Aurora Humanitarian Initiative to honor the memory of those who acted individually and at great personal risk to save our Armenian forefathers, one would hope that the case of Liman von Sanders would come to their attention. There are no monuments to be reconstructed, merely the recognition of the honorable deeds he performed in a spirit of humanity.

(Sources: “Preußens Gloria,” by Christina Rietz, Die Zeit, May 25, 2018, “Aufbau der Garnisonkirche: Ein Armenier dankt deutschen Soldaten,” Potsdamer neueste Nachrichten, June 2, 2017, June 21 and 24, 2018, Wikipedia, http://garnisonkirche-potsdam.de/nc/ https://auroraprize.com/en/stories/detail/regular/114/noubar-afeyan)

(This article is published in https://mirrorspectator.com/2018/07/19/gratitude-from-the-diaspora/ )

Pubblicazione gratuita di libera circolazione. Gli Autori non sono soggetti a compensi per le loro opere. Se per errore qualche testo o immagine fosse pubblicato in via inappropriata chiediamo agli Autori di segnalarci il fatto e provvederemo alla sua cancellazione dal sito